The incredible miracle in poor country development

This graph shows that over the last three decades or so, the global poor and middle class reaped huge gains, the rich-country middle-class stagnated, and the rich-country rich also did quite well for themselves.

You also have the poverty data from Max Roser, showing how absolute poverty has absolutely collapsed in the last couple of decades, both in percentage terms and in raw numbers of humans suffering under its lash:

This is incredible - nothing short of a miracle. Nothing like this has ever happened before in recorded history. With the plunge in global poverty has come a precipitous drop in global child mortality and hunger. The gains have not been even - China has been a stellar outperformer in poverty reduction - but they have been happening worldwide:

The fall in poverty has been so spectacular and swift that you'd think it would be a stylized fact - the kind of thing that everyone knows is happening, and everyone tries to explain. But on Twitter, David Rosnick strongly challenged the very existence of a rapid recent drop in poverty outside of China. At first he declared that the poor-country boom was purely a China phenomenon. That is, of course, false, as the graphs above clearly show.

But Rosnick insisted that poor-country development has slowed in recent years, rather than accelerated, and insisted that I read a paper he co-authored for the think tank CEPR, purporting to show this. Unfortunately this paper is from 2006, and hence is now a decade out of date. Fortunately, Rosnick also pointed me to a second CEPR paper from 2011, by Mark Weisbrot and Rebecca Ray, that acknowledges how good the 21st century has been for poor countries:

The paper finds that after a sharp slowdown in economic growth and in progress on social indicators during the second (1980-2000) period, there has been a recovery on both economic growth and, for many countries, a rebound in progress on social indicators (including life expectancy, adult, infant, and child mortality, and education) during the past decade.

Weisbrot and Ray, averaging growth across country quintiles, find the following:

By their measure, the 2000-2010 decade exceeds or ties the supposed golden age of the 60s and 70s, for all but the top income quintile.

I'm tempted to just stop there. First of all, because Weisbrot and Ray are averaging across countries, rather than across people (as Milanovic does), China is merely one single data point among hundreds in their graph above. So the graph clearly shows that Rosnick is wrong, and the recent unprecedented progress of global poor countries is not just a China story. Case closed.

But I'm not going to stop there, because I think even Weisbrot and Ray are giving the miracle short shrift, especially when it comes to the 1980s and 1990s.

See, as I mentioned, Weisbrot and Ray weight across countries, not across people:

Finally, the unit of analysis for this method is the country—there is no weighting by population or GDP. A small country such as Iceland, with 300,000 people, counts the same in the averages calculated as does China, with 1.3 billion people and the world’s second largest economy. The reason for this method is that the individual country government is the level of decision-making for economic policy.

Making Iceland equal to China might allow a better analysis of policy differences (I have my doubts, since countries are all so different). But it certainly gives a very distorted picture of the progress of humankind. Together, India and China contain well over a third of humanity, and almost half of the entire developing world.

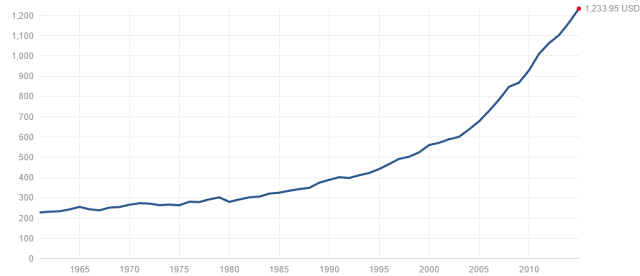

And when you look at the 1980s and 1990s, you see that the supergiant countries of India and China did extremely well during those supposedly disastrous decades. Here's Indian real per capita GDP:

As you can see, during the 1960s, India's GDP increased by a little less than a third - a solid if unspectacular performance. From 1970 to 1980 it increased by perhaps a 10th - near-total stagnation. In the 1980s, it increased by a third - back to the same performance as the 60s. In the 1990s, it did even better, increasing by around 40 percent. And of course, in the 2000s, it has zoomed ahead at an even faster rate.

So India had solid gains in the 80s and 90s - only the new century has seen more progress in material living standards. Along with Indian growth, as you might expect, has come a huge drop in poverty (and here's yet more data on that).

Now China:

The 60s were a disaster for China, with GDP essentially not increasing at all. It's hard to see from the graph, but the 70s were actually great, with China's income nearly doubling. The 80s, however, were even better, with GDP more than doubling. The 90s were similarly spectacular. And of course, rapid progress has continues in the new century.

So for both of the supergiant countries, the 80s and 90s were good years - better than the 60s and 70s. Collapsing these billions of people into two data points, as Weisbrot and Ray do, turns these miracles into a seeming disaster, but the truth is that as go India and China, so goes the developing world.

Now let's talk about policy.

My prior is that the 80s and 90s look bad for poor countries in Weisbrot and Ray's dataset - and the 70s look great - because of natural resource prices. Metals prices rose steadily in the 60s, surged in the 70s, then collapsed in the 80s and 90s:

Oil prices didn't rise in the 60s, but boy did they soar in the 70s and collapse in the 80s and 90s:

The same story is roughly true of other commodities.

My prior is that the developing world contains a large number of small countries whose main industry is the export of natural resources, and whose economic fortunes rise and fall with commodity prices. Just look at this map of commodity importers and exporters, via The Economist:

Yep. Most of the countries in the developing world are commodity exporters...with the huge, notable exceptions of China and India.

So I strongly suspect that Weisbrot and Ray's growth numbers are mostly just reflections of rising and falling commodity prices. Averaging across countries, rather than people, essentially guarantees that this will be the case.

Do Weisbrot and Ray recognize this serious weakness in their method? The authors mention commodity prices as an explanation for the fast developing-country growth of 2000-2010, but completely fail to bring it up as an explanation for the growth during 1960-1980. In fact, here is what they say:

[T]he period 1960-1980 is a reasonable benchmark. While the 1960s were a period of very good economic growth, the 1970s suffered from two major oil shocks that led to world recessions—first in 1974-1975, and then at the end of the decade. So using this period as a benchmark is not setting the bar too high.

But the oil shocks, and the general sharp rise in commodity prices, should have helped most developing countries hugely, not hurt them! Weisbrot and Ray totally ignore this key fact about their "benchmark" historical period.

So I think the Weisbrot and Ray paper is seriously flawed. It claims to be able to make big, sweeping inferences about policy by averaging across countries and comparing across decades, but the confounding factor of global commodity prices basically makes a hash of this approach. (And I'm sure that's not the only big confound, either. Rich-country recessions and booms, spillovers from China and India themselves, etc. etc.)

As I see it, here is what has happened with poor-country development over the last 55 years:

1. Start-and-stop growth in China and India in the 60s and 70s, followed by steady, rapid, even accelerating growth following 1980.

2. Seesawing growth in commodity exporters as commodity prices rose and fell over the decades.

Of course, this means that some of the miraculous growth we've seen in the developing world since 2000 is also on shaky ground! Commodity prices have fallen dramatically in the last year or two, and if they stay low, this spells trouble for countries in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Their recent gains were real, but they may not be repeated in the years to come.

But the staggering development of China and India - 37 percent of the human race - seems more like a repeat of the industrialization accomplished by Europe, Japan, Korea, etc. And although China is now slowing somewhat, India's growth has remained steady or possibly even accelerated.

So the miracle is real, and - for now, at least - it is continuing.

Comments

Post a Comment